COLLECTIVES

COLLECTIVES refers to the groups and partnerships that seek an architectural-urban project for shared activities and community building. Constituted by a voluntary group of people who organize around shared values and mutual understandings, this kind of collective seeks to improve the way they live—shaping their community, creating a social support system, practicing common ideals and principles, affording better living conditions for their means, and facilitating opportunities to establish friendships.

While in contemporary society the use of the term “community” often refers to groups established within the digital realm, our aim here is to examine the physical manifestation of such notions through their architectural and urban implications. While recent developments in sharing economies, community-based exchange, and collaborative platforms — enhanced and made easier to use through digital technologies — have greatly contributed to expanded notions of the term, these notions should also be considered through a spatial lens. This is not, however, to suggest that ideas of community-based sharing are completely new — on the contrary — but rather to witness the return to ideas of collaboration and sharing which are to be found in the past.

During the past decade we have experienced an exponential increase in various types of sharing platforms. Rideshares, Airbnb, WeWork, TaskRabbit, and many more applications and platforms, spanning almost all activities of everyday life, are being established and used by more and more people. Although debate persists regarding the nature and place of what has been generally referred to as the sharing economy, it is widely agreed that existing socio-economic structures are being altered. Arun Sundararajan describes the sharing economy as situated somewhere between the market and gift economies, “an interesting middle ground between capitalism and socialism — that also appears to lend itself to fulfilling the desires and needs of people who identify with the extreme ends of both the economic and political spectrums.”[1]

This middle ground questions the divide not only between the sociopolitical structures of capitalism vs. socialism, market vs. gift, individual vs. collective, etc., but more importantly between private and public space. What have become everyday experiences such as riding in a stranger’s car (Uber/Lyft) or sleeping in someone’s bed (Airbnb/Couchsurfing/Love Home Swap) reflect the collapse of conventional public-private boundaries. Examples of new use patterns abound, relating to daily activities of food, transportation, diversified labor, personal services and more. Causing us to question the traditional definitions and characteristics of the public-private dichotomy, these practices are re-defining public and individualized space. Interestingly, an examination of the actual physical spaces in which these new modes of sharing take place reveals that most have been utilizing existing forms, appropriating old building typologies and infrastructure rather than inventing new ones. In other words, architecture and the city have mainly adapted to these patterns and, in most cases, have not yet generated new, better-suited models and spaces.

In parallel to the increase in the sharing of private spaces, i.e. opening them to “public” use, we can identify an erosion of traditional forms of public space — a longer-term retreat and gradual diminishment of the power of the public realm. This process has been associated with a growing civil distrust in public institutions, particularly in government, a condition exacerbated by the lack of public funds to support such institutions. This civic distrust is clearly evident in the fresh wave of social movements, amongst them the Commons movement, which seeks to recover new “publics” outside their historic conventional forms. It perceives many traditional forms of urban public space as privatized or overly controlled and supervised to the point that they have lost a sense of “publicness” —their political essence as spaces of action, spontaneous organization, and emergent social practices.[2]

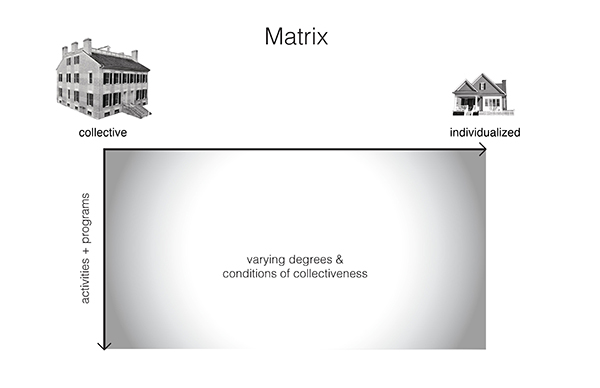

COLLECTIVES asks how architecture and urbanism could respond to new modes of sharing. Through examining historic and present case studies, we interrogated the role of design in imagining and shaping new collective forms of life, work, and leisure. We propose a paradigm shift in the way public-private relationships are thought of, moving from the binary division of public vs. private ownership to a field condition of varying degrees of collectiveness. I referred to these varying degrees, or “in-between” conditions, as comprising an expanded “middle ground” of social spaces, what we coined as a spatial gradient: a spectrum of conditions that go beyond the conventional terms of “semi-public” and “semi-private.” In many ways this shift is difficult to imagine, especially within the context of the United States, where the idea of private property is deeply rooted as a fundamental civic right that carries both freedom and liability (our current legal system and practice of lawsuits for example demands precise boundaries between ownerships to determine responsibility). The search for collective forms is as much a cultural exploration into patterns of behavior and occupation of space as it is a project of architecture and urban form. It first and foremost relies on strengthening social norms and accepting that in between what is “mine” — that which I am responsible for—and what is “theirs” — that which supposedly does not concern me—there lies a potential “ours,” of which one shares and partake in.

This spatial gradient facilitated the imagination of a variety of spaces that would address the “ours” and aid in the creation of new types of spatial modes, urban conditions and building types.

[1] Arun Sundararajan, The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-based Capitalism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016), 45.

[2] For further reading see: Heidi Sohn et al., “Commoning as Differentiated Publicness,” Footprint: Delft Architecture Theory Journal 16 (2015): 1.