Archipelago of the Negev Desert:

A Temporal / Collective Plan for Beer Sheva

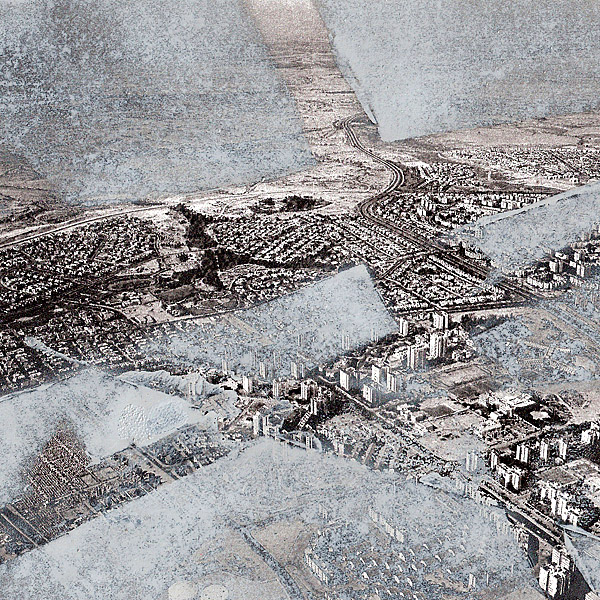

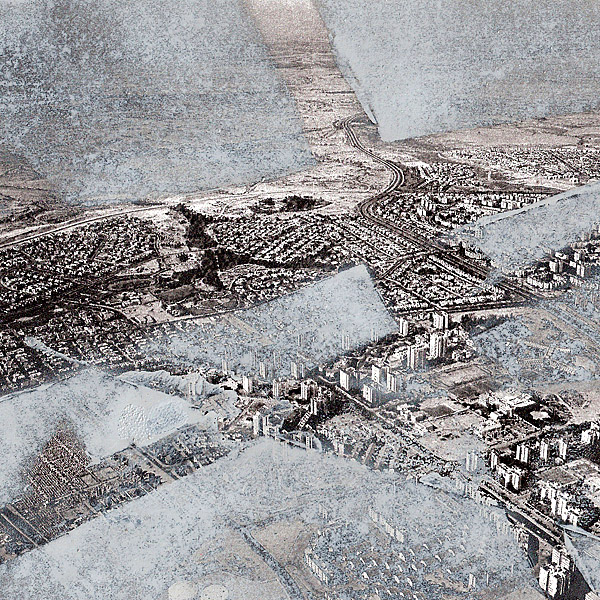

Countless efforts to establish a dense and active city center for Beer Sheva have failed. Its extreme desert climate, culture, and socio-political conditions have not allowed the development of a traditional city core.

Within the early years of the Israeli State, and under the motto of ‘blooming the desert’, Beer Sheva –located in the south of the country, found itself part of the new Zionist frontier, which sought to combine advanced agriculture with the national mission of settling new Jewish communities in the Negev desert. Beer Sheva became the emblematic tabula rasa. Its peripheral location and desert setting served as a site of urban and architectural experimentation. Notable were the attempts to appropriate modernist concrete housing slabs to the extreme arid climate. The construction of Beer Sheva went in hand with State objectives to push the nomad Bedouin tribes outside the city. Historically, during the early 20th century, under Ottoman rule, the city was conceived as a regional center of exchange and gathering, that came to life just a few days a week, when activated by the nomadic tribes (Bedouin) that would come in to setup the market (on Wednesdays) and congregate for joint prayers (Fridays).

The desire to turn the city into a larger fixed urban center for a permanent modernized Jewish population met with too many difficulties: that of drawing new inhabitants to the city, as well as lack of government support which for political-strategic reasons favored other towns and settlements situated closer to territorial conflicts, and thus considered a higher priority for national security. Later attempts to house new immigrants in the city increased social and ethnic separation, leading to segregated communities –utterly disconnected from any sense of urban identity; they are still referred to by the alphabet describing the land plots on the city’s master plan (e.g. neighborhood ‘c’, neighborhood ‘d’, etc)

The fact remains that although situated in a beautiful desert landscape, in an area with access to water, Beer Sheva is currently one of the most run down cities in Israel. Inhabited by diverse groups (Ethopian Jews, 1990’s Russian immigrants, older generation settlers, etc, etc) in neighborhoods socially set apart from each other, it has all the infrastructure of a populated urban environment yet it lacks the sense of city - a notion that led to its nickname as the ‘non-city’. Beer Sheva’s architecture and urbanism disregards its unique natural setting, missing opportunities to benefit from this resource. This attitude towards the environment is also reflected through the attitude towards the Bedouin tribes -- most of them currently occupying areas within a 20 km radius of Beer Sheva, with a population equivalent to the number of the Israelis living within the current cities boundaries.

Public Voids, Temporal Programs

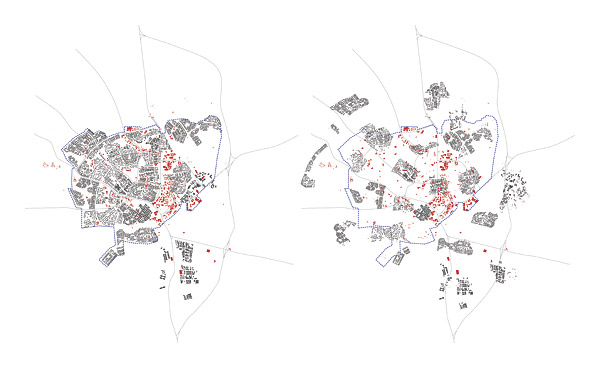

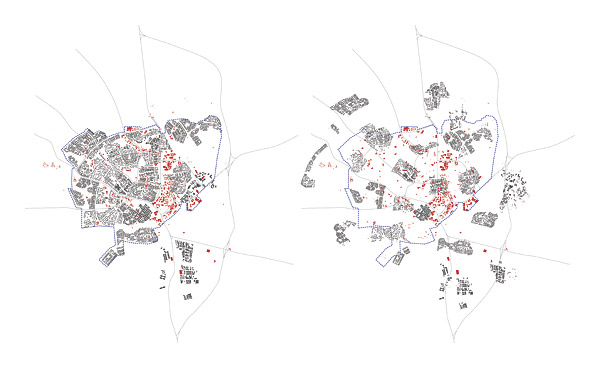

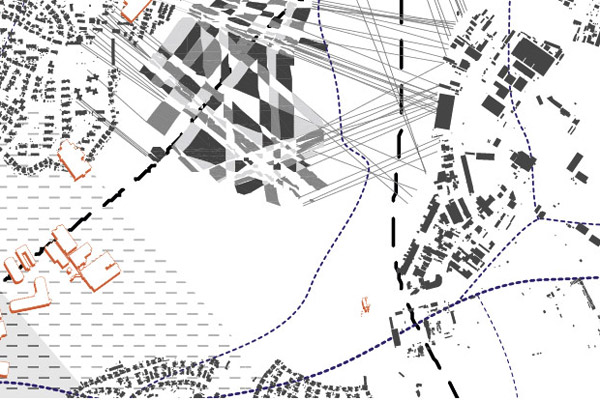

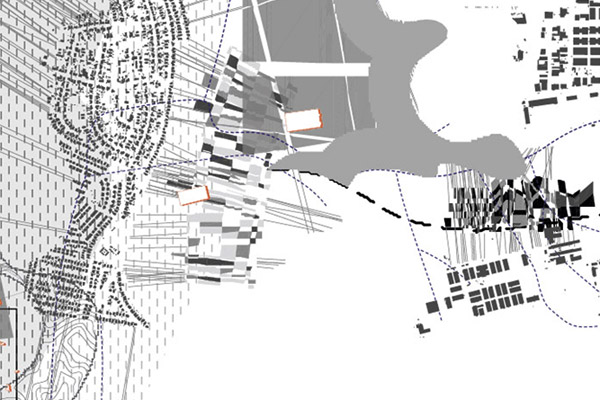

Departing from the understanding that Beer Sheva's lack of center is one of its inherit conditions, this proposal introduces a de-centralized urban scheme, in which the city is fragmented into distant neighborhoods, allowing the desert to flow through it.

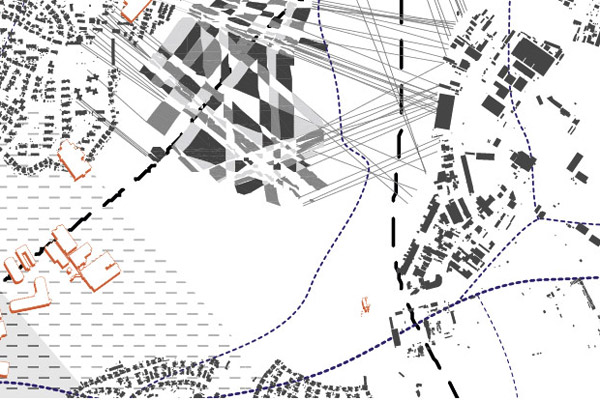

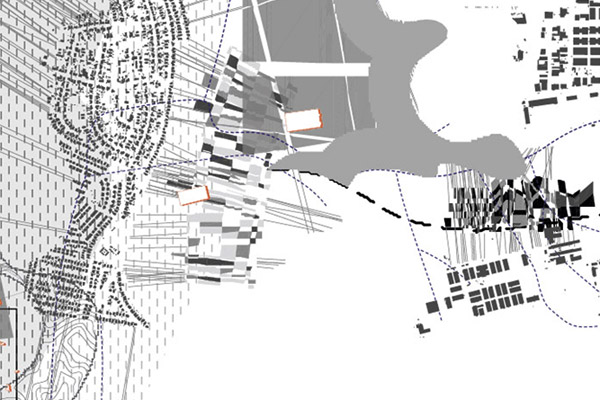

These neighborhoods are set apart from each other, becoming 'islands' floating in a desert landscape. The existing inner voids are expanded to a point where they become continuous; creating an ‘ocean’ of desert space in which the island-like neighborhoods are scattered. This ‘ocean’ of unclaimed land becomes a transient public space. Within it designated collective areas/zones are formed, each inscribed with a new temporal program, with its own cycle –timeframe of activity. These collective zones/program intersect, overlap, using in many instances the same space at different times. The city’s existing public buildings are incorporated within these areas, mediating between the neighborhoods.

From an environmental, ecological point of view – this inner void prevents the city from becoming one large mass, allowing the desert and at the same time the city to 'breathe'. The Bedouin tribes take part in activiating this space, as a place of passage from one part of the desert to the other.

Segregation, usually understood negatively as interrupting the livelihood of people, here allows co-existence. It perpetuates flow and enables distinct modes of living and diverse groups of people to occupy the same space.

The notion of the urban is established through links and connections between nodes of activity, and the juxtaposition of the collective programs with smaller neighborhood clusters - - all surrounded inside and out by the unique desert landscape on which Beer Sheva has until now turned it’s back.

Project team: Yonatan Cohen, Kate Snider